Loved and loathed in equal measure, AI is bound to change the way we make and see film; Redmond Bacon talked to the technology champions, the early adopters and the end-users during the Industry Innovation Forum at the 28th Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival.

The Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival is making waves with Susi,** a highly knowledgeable AI assistant** who makes searching the vast interweaving network of an A-list festival, with 100s of films and events over two and a half weeks, easy. For example, when one asks Susi about forums on AI at the festival, it responds with a recommendation that we should attend "Industry Innovation Forum Tallinn 10!: Looking back, envisioning the future for European content and media."

Susi is one of the most high-profile uses of AI at a film festival so far, a great and simple example of how this technology can make our lives easier. Yet generative AI - whereby the machine can generate the backgrounds for a VFX shot, create new images, write a screenplay, and even generate an entire movie from beginning to end - provides much thornier ground for discussion. While some filmmakers decry the end of human creativity, others see an opportunity to democratise the creative process.

Whatever your thoughts on AI, the projected rise is startling, with generative AI in film expected to grow from 351 million in 2023 to a whopping $3.7 billion in 2033 according to marketresearch.biz. This is expected to have a major knock-on effect on who works in film with industries such as animators (55%), VFX artists (50%) and voice actors (41%) believing that their jobs will be impacted in the next two years. The effects in the USA (where AI deregulation is on the new Trump administration's agenda, including a planned executive order to repeal Biden's compliance policy) are almost certain. The United States currently leads the way with 45.4% of the generative AI in cinema market.

The current question, and the purpose of summits such as this year’s Innovation Industry Forum, is whether Europe, which consultancy firm AI Caramba founder Matthew Blakemore calls “the leader in terms of regulation” will keep up this trend or fall by the wayside just as AI changes the world of cinema (for good or for ill)? And if Europe, known for purposeful, auteur-driven cinema instead of film-by-committee, decides to embrace AI workflows, does this bode well for the world’s seventh art form?

Makers, not takers

The Innovation Industry Forum, now celebrating its 10th year, is presented in conjunction with the Tallinn Digital Summit, and hosted by Estonian Prime Minister Kristen Michal. It posits Estonia, which is often ranked near the top in digital development in Europe, as a leader in innovative thinking. This makes Tallinn the obvious place to discuss the potential of AI in the filmmaking world. The Forum is part of the Industry@Tallinn & Baltic Event.

But Estonia and forums such as these might be an outlier in Europe, where strict regulation and EU law means that generative AI isn’t flourishing in the same way as in North America.

Future Media Hubs advisor Anssi Komulainen attended the Event. He cites Coca-Cola’s very recent and extremely controversial AI-generated advert, created by Bain & Company and WPP Open X, and also involving Essence Mediacom, BCW, Ogilvy and Obviously. Leaving the extremely ugly visuals and overall dread-inducing aesthetic behind, this was developed and created without any European involvement, leading Komulainen to state that AI in “media is clearly not represented in the European innovation agenda”.

This is borne out by the Draghi report, where 60% of EU companies find regulation an obstacle to investment, with creative sectors among the most impacted. This is due to a variety of reasons, such as the longer times it takes to comply with transparency, data protection, cybersecurity and IP laws than our American counterparts, as well as the higher license fees for training data.

Blakemore concurs, saying that, "Europe remains largely a taker, not a maker, of leading generative AI models due in part to overregulation stifling its own innovative startups. Like [European Commission President] Ursula von der Leyen and [French President] Emmanuel Macron, I am calling for change to help Europe compete with the dominance of U.S.-based tech."

It appears that Europe should be looking forward to adopting AI frameworks at a higher rate, yet the continent should be extremely cautious about the high level of deregulation, with even looser AI guardrails, that a new Trump administration, guided by the highly libertarian Elon Musk, promises. This is especially true when you consider the jobs in the film industry at risk as well as intellectual property concerns about the data platforms such as Dall·E 2, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney use to train their images.

Filmmakers out?

Filmmakers have fears and reservations about the implementation of AI. Irish filmmaker Seán Gallen, director of short film The Head on Him (which just premiered at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival) is concerned about the impact on the workforce: “Generative AI is being promoted as a powerful tool that will help us tell better stories but in reality, it's being heavily promoted because companies are excited to cut humans out of the creative process in order to save money.”

This is borne out by the statistics themselves, with consultancy firm Bain estimating that the introduction of AI could reduce the cost of filmmaking by an impressive 20%. So people in the industry are rightly concerned that AI will replace their jobs while providing an inferior version of the same project.

Heavily AI-generated works that do appear, such as the OpenAI Sora-produced Air Head (Shy Kids, 2024; pictured above) or the trailer for the upcoming Next Stop Paris (director unknown), are currently characterised by a weird and glossy aesthetic and un-lifelike movements, a deep sense of needlessness and a trip down an uncanny valley, posing the question: do we even want to see the name of filmmakers replaced by clunky corporate slogans, or simply left blank?

Baby out with the bathwater?

Matthew Blakemore is positive about the impacts of generative AI in cinema, pointing out that, "tools like Adobe’s generative AI tackle tasks like object removal and tedious edits, making advanced capabilities more easily accessible".

The cheaper access to creation might also be a way for Europe - and the rest of the world - to catch up with North America. As Blakemore says: "Generative AI significantly reduces costs by automating tasks like creating visual effects or virtual locations, which can be done at a fraction of traditional expenses. This allows smaller studios to produce high-quality films and compete globally."

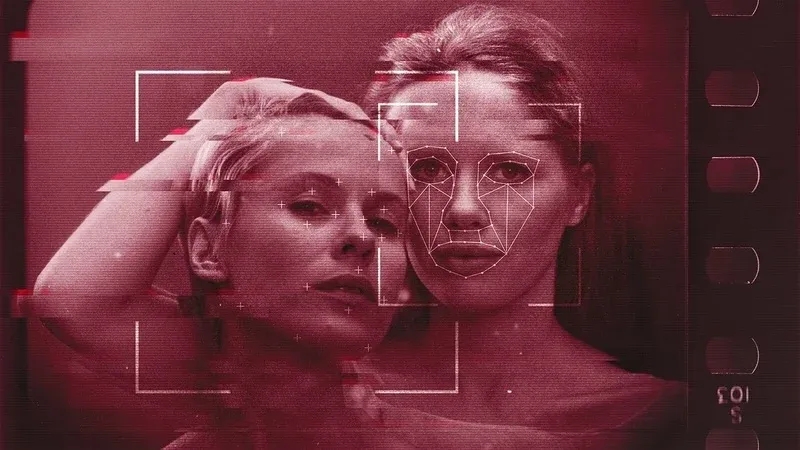

Generative or notm AI is already making an impact in smaller ways and has already been used in Hollywood productions,. Notable examples include David Fincher using it to clean up dialogue in The Killer (2023), George Miller using it in Furiosa (2024) to blend two characters’ faces together (pictured at the top of this article). It generated far more outrage when AI was used to create clunky graphics for cutaways in Late Night With the Devil (Cameron Cairnes, Colin Cairnes, 2023) and the opening credits of Marvel's miniseries Secret Invasion (Ali Selim, 2023). But like any tool, AI becomes only a source of outrage when people notice who shoddy it is. Therefore, in the future, AI might become like CGI: when you notice it, it’s bad, but if you don’t, it could have its uses.

Get your hands dirty

Industry@Tallinn is ahead of the game when it comes to teaching filmmakers how to use AI. This year's inaguaral Generative AI Atelier offered a three-day workshop in order to help equip filmmakers with the tools they need to use generative AI in their work.

Marge Liisker, Head of Industry@Tallinn, heard our concerns about jobs being replaced, but also saw the AI atelier as a significant opportunity for filmmakers: “I, of course, know that there are some areas where AI would fully replace people. [With the AI Atelier] we are now concentrating more on tools that help filmmakers have a vision, write and compose pitch decks. These things can really help them to better express their ideas.” She cites visualisation as a great example: “Let’s say, in order to shoot a trailer, you can maybe generate a one-and-a-half-minute trailer with the help of AI”.

Perhaps Seán Gallen may have benefited from the lessons learned in the workshop. The use of AI is seen during a dream sequence in The Head on Him, a homage to the dreamy ancestral plains of Africa. Gallen - and its promise of easy delivery - after running out of budget. “Firstly, we were feeding it prompts to generate images of Lagos and then rural Western Nigeria; people outside their houses, working, commuting. [But] it kept giving us images of safari plains and villagers in straw skirts with bones through their noses.” On top of this “limited and reductive” view of West Africa, “it kept enhancing the chest of the grandmother character without being prompted to do so. We tried lots of different things to get it to stop but in the end, we had to tell the AI that the character was a man”.

The experience has not left Gallen with a positive view of AI’s potential in comparison to a human creator: “We managed to produce some nice backdrops and movement but it was much more difficult, expensive and time-consuming than I expected. If I had worked with a human illustrator, it would have been easier to convey the vision, work through examples and feedback rounds to produce something more arresting.” This view of artistic quality is supported by the public themselves, with a Deloitte survey showing that 70% of people would rather watch a film or television show created by a human than a machine.

While the experience didn’t fully satisfy him, it does show that, in a limited way, and with the right prompts, AI can be used as a tool to help emerging filmmakers develop assets for their works. This is especially worth considering as the technology improves. As Technologist & Futurist, Sandar Saar, says at the Forum, “Every six months, AI capabilities are doubling. That completely changes the solutions we have access to.”

This leaves other filmmakers potentially considering using it in the future, such as Zulfikar Filandra, whose short Victory played in the Shorts competition, “I would use it for sure if I could figure out a way to create something interesting with it,” telling of a potential idea about a friend who is his potential doppelgänger: “I’m considering merging our faces via AI into a new entity made of us two”.

What about film festivals?

Talking of merged faces, earlier this year, in a move to promote conversation, Göteborg Film Festival in Sweden screened Another Persona (2024; pictured above). Developed by producer Paul Blomgren DoVan, Face Tool Operator Henrik Svilling, and Gothenburg Film Studios CEO Daniel Lägersten, this one-off version of Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966) superimposed Finnish actress Alma Pöysti’s face onto Liv Ullmann. Only screened once, it was intended to spark discussion about the use of AI in cinema, but ultimately came off as a gimmicky promotional tool.

Still, specific film festivals have already popped up to meet this demand for AI-generated content, with the bigger names innovating with ways to support this emerging need. The city of Cannes announced Cannes Immersive, serving as a showcase for “the most exceptional immersive creations, whether assisted or generated by AI,” while EFM at Berlinale focussed specifically on AI this year. Nonetheless, a mostly or fully AI feature has yet to premiere at a major A-list film festival. And it may be some time before we see one.

Triin Tramberg watches 100s of submissions a year when programming her First Feature Competition. She says that she is yet to hear about “a film that is fully AI-made and is good.” And would she program an AI film if it was anyway decent? “Yes, but I think it would be in a special screening. Not in competition.”

Bridging an ocean

There is an evident ocean of differences between filmmakers' and programmers’ views of AI versus the thought-leaders at the Forum, which unfortunately didn’t invite any directors themselves to share their opinions of this future technology. But Blakemore understands the challenges AI evangelists will face, saying that "Convincing AI skeptics requires addressing environmental, artistic and ethical concerns. People can justifiably be skeptical, but with transparency, responsible practices, and AI positioned as a tool to empower rather than replace human creativity, we can build trust and unlock its transformative potential."

This discussion is not going to die any time soon. According to Statista, AI will experience an year-on-year growth 46.7% until 2030 across the European continent, making it likely that the adoption of these technologies will become more and more commonplace. Expect plenty of dissatisfying and ugly AI-created works, but also quicker workflows, lower overheads and simply more content out there in the market. Finding diamonds in the rough will be immensely difficult, but curators, tastemakers, programmers and critics have always found what's worth preserving in a vast sea of filmmaking content. It's up to filmmakers who choose to embrace AI not to rush out their products, but experiment in order to create something truly innovative. A hybrid of AI and the human brain.

This article was made possible by Otter AI, which automatically transcribed conversations with Triin Tramberg and Marge Liiske, saving the author time and effort.

This piece is a cross-publication in partnership with DMovies.org.